why are there weirdos in my comments?

on Substack's indifference towards harmful content and men hating women

Comments for this post are disabled. In Chappell Roan’s words, this isn’t a conversation. I have no interest in what people (you know who) think about this piece. If you have something nice to say about it, my dm’s are open <3

Part I: What’s happening on Substack?

Since becoming a social media app with the inclusion of notes into the website, Substack has become a place similar to Twitter—filled with people looking for attention, virality, or just to be noticed.

Even though racist, misogynistic, and offensive comments are predominant on all social media apps, Substack felt different—a place where this behavior wasn’t common. I felt safe in here. That was until I started seeing men flooding female writers’ posts with overly sexual comments. At first, I only saw a couple of comments here and there, yet lately, the number has exponentially grown.

After speaking to other women about their experiences with racism, homophobia, and misogyny on this app, I realized the issue is so much bigger than I thought. The real concern is that Subsatck has become a safe place for the far-right and other extremists, and their creators allow it.

Part II: Substack’s stance

Alex Hern wrote for The Guardian earlier in the year about how Substack faced a user revolt “after its chief executive defended hosting and handling payments for “Nazis” on its platform, citing anti-censorship reasons."

Even after big creators on the platform threatened to leave if the company didn’t fix the issue, their leaders stood firm on their decision to allow any opinion to have a place on the platform, saying:

“As we face growing pressure to censor content published on Substack that to some seems dubious or objectionable, our answer remains the same: we make decisions based on principles not PR, we will defend free expression, and we will stick to our hands-off approach to content moderation.”

Their response wasn’t only unfortunate, but it made me feel sick. Substack seems more worried about being “impartial” and profiting from content (even when it’s harmful) than protecting its users from hateful and extremist views. To me, this is a clear case of capitalist greed. Substack’s board has no interest in protecting its users from violent content, as long as it fills their pockets.

Later in the article, Hern mentions Talia Lavin, a journalist who left Substack after its founders stated that censoring “sites that publish extreme views was not a solution to the problem and instead made it worse.” In her new newsletter, Talia wrote about why she left, arguing:

I must admit that there's a fair amount of anger and resentment that comes along with this decision—anger at feckless rich crypto-fascists like Hamish McKenzie of Substack, and his many Silicon Valley peers, who all seem to subscribe to the notion that race-based hatred is just a simple quirk of the marketplace of ideas.

Part III: how I became a target for misogynists on this platform

I’ve been sexually harassed since I was in middle school. I have dealt with it for more than half my life, and still, every time it happens, it feels like the first time. Anger, fear, and shame are the predominant emotions every woman feels when harassed. No matter how much we are used to it, it never becomes normal.

Every time I go outside, there is a man on the streets who feels he has the right to scream, whistle, talk to, and even follow me to make comments about my looks. I am used to this behavior outside. But when I’m home, I feel safe. Or at least that’s how I felt until this week.

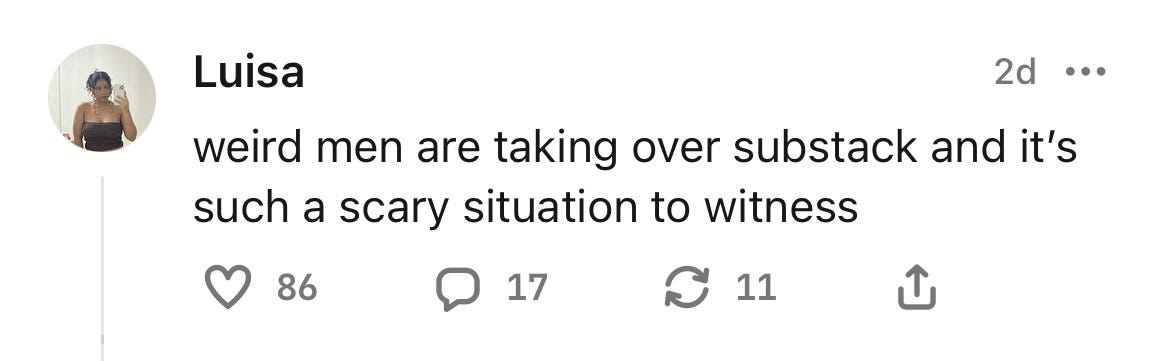

A few days ago, I posted a note that said:

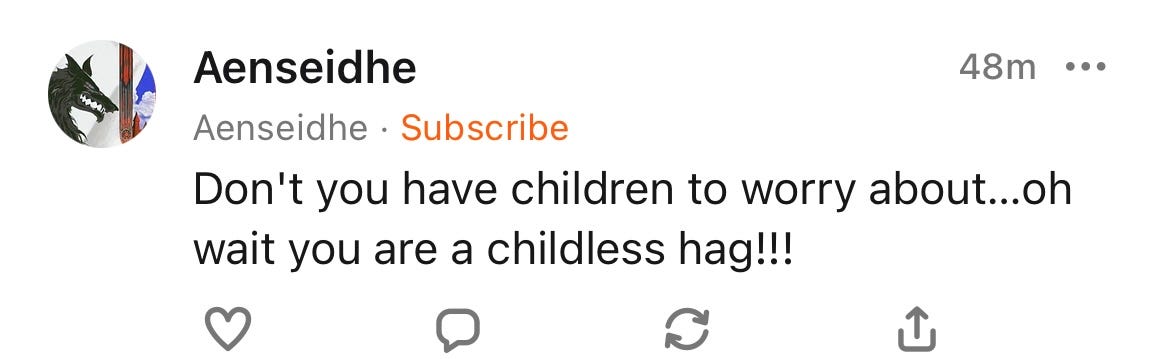

The first reactions were from people, mostly women, agreeing with me. But then, the inevitable happened: Incels found my note. One by one, they filled my comments with racial slurs and misogynistic comments.

When I read the comments, my first response was to laugh. They were calling me ugly, slutty, and other things that I have been called before. I wasn’t fazed. I found it funny that they were so pressed about my use of the word “weird.” That was until I read someone calling me the N-word. A slur I have never in my life been called since I live in Colombia. When I read the comment, I couldn’t believe my eyes. I was so shocked that my mouth was left wide open for a whole minute.

When I called men "weird,” I was referring to the hundreds of them leaving overly sexual comments on female writers’s posts. Until that moment, I hadn’t encountered any racist comments. The thing is, we tend to think that because we don’t see harmful comments on our feed, they don’t exist. But just because it hasn’t happened to you doesn’t mean it is not happening to other people. Bigots are everywhere, lurking around, waiting for the perfect moment to make themselves notable. We forget that. I did.

It’s been said that a man’s worst fear is a woman laughing at them. I guess my note made insecure men feel bad about themselves. They thought I was mocking them by calling them "weird.” But I wasn’t even laughing in my note. I was expressing worry about a serious issue, and I got harassed for telling the truth.

I wish I could say that I wasn’t surprised, but I was. I encountered so many more violent men than I thought were on Substack. All it took for them to make themselves noticed was to call their behavior weird, which they fought back by being… weird.

Yet, nothing bothered me more than the two women on my posts telling me to stop complaining and to move on with my life. They said that the only solution to this was to block and act like these men were not real and that censorship had no place on Substack. That I was immature for complaining.

To those women, I want to say: I hope nothing like this ever happens to you and that one day you can develop an ounce of sympathy and a fucking backbone.

Part IV: Other cases of misogyny on Substack

I wish this behavior wasn’t usual on this platform. I wish there was a safe place for women in this violent world. I wish Substack cared more about their user’s safety than about money. But reality differs.

Platformer wrote about the controversy:

The company will not change the text of its content policy, it says, and its new policy interpretation will not include proactively removing content related to neo-Nazis and far-right extremism. But Substack will continue to remove any material that includes “credible threats of physical harm,” it said.

This means that the only scenario in which Substack will remove far-right extremists or any type of harmful content is when people are in physical danger. As if online threats aren’t real. As if cyberbullying isn’t real.

There are so many women, POCs, and queer people who have become the target of violent men on this website. They have been sexually harassed and called racial and homophobic slurs. Worst of all, they will continue to be targets as long the right to do it exists within this platform.

This week, Sarah Cucchiara from people’s princess and Amanda from Certified got their latest piece stolen, plagiarized, and mocked by a man. Word for word, he replicated their entire work and only changed the word “men” for “women.” This is a vile act that can only be understood as pure misogyny. The worst part? Substack allows it, all in the name of “free speech”.

I feel outraged for them. Both Sarah and Amanda work very hard to publish quality content on their publications. I can’t imagine how awful this must feel, and I hope they know their work’s value will never be diminished by insecure, sexist men’s attempts to ridicule it.

Part V: The censorship fallacy

Censorship, by definition, means the suppression of speech and other forms of communication. Historically, it has been a tool used by authoritarian regimes to silence the opposition. To oppress people who go against the norm. But the far right is not an oppressed group. No matter how hard they try to make themselves the victims, they are not in danger. More often than not, they are the ones who are violent towards minorities.

Still, they have weaponized the term to use in support of their victimization discourse, and Substack’s directors reinforce their argument. Amidst the platform user revolt, Hamish Mckenzie, Substack’s co-creator, said:

We believe that supporting individual rights and civil liberties while subjecting ideas to open discourse is the best way to strip bad ideas of their power. We are committed to upholding and protecting freedom of expression, even when it hurts.

Mckenzie’s statement is ambivalent, even if it tries to be neutral. Banning far-right content on your platform is not censorship or a way to protect civil liberties. In fact, this stance allows harmful ideas to be spread all over the platform with little to no consequences. Jonathan M. Katz, wrote on the subject for The Atlantic, saying:

Substack’s definition of free speech goes beyond welcoming arguments from across a wide ideological spectrum and broadly defending anyone’s right to spread even bigotry and conspiracy theories; implicitly, it also includes hosting and profiting from bigoted and conspiratorial content.

Now, where do we go from here? First, we need to acknowledge that neutrality is a political position. When you choose to stay neutral, you are choosing to do nothing. When you decide to do nothing, you become an accomplice.

We also need to stop making excuses. The argument that censoring extremist views on social media aggravates the issue is simply not true. Of course, if extremists are banned from this app, they will eventually find other places to share their opinions, but this is still not a good argument for allowing them to have a platform on Substack. There shouldn’t exist a place outside or in the digital world in which neo-nazis and other extremists feel safe to share their racist, misogynistic, and violent opinions. Contrary to what Mackenzie and his peers think, not everyone deserves to share their opinions. Especially not when it’s harmful to historically oppressed communities.

Conclusion

I would like to say that after all, I wasn’t affected by the comments and that I moved on with my day as it was. I will be lying. I decided that for my mental health, the best I could do was to delete the note and stop the discourse from the root. I wasn’t going to let these men get to me. I deleted the Substack app from my phone. I watched a movie. I forced myself to go to the gym for my dance class to take my mind off it. But as soon as I left the gym, my mood dropped.

I started thinking about all of the horrible things I was called. I felt dirty and empty. I couldn’t understand why men hate women so much. Mostly, I didn’t like that in the end, they got what they wanted; they hurt me. But then I started to think about all the amazing women (and some men) who reached out to check on me. If you were one of the people who left me a comment or sent me a DM, thank you. I am forever grateful. You made me remember that I am not alone.

I’m not sure when I will re-download the app or if I ever will. For now, the best thing for me is to reduce my use and focus my energy on writing new pieces and living my life outside of the digital world.

I know I don’t have all the answers, and I encourage you to do more research on the subject if you are interested in how we can fight these views to spread on Substack. The only way through is together.

See you soon,

Luisa

Further reading:

Substack articles on misogyny

did you say no? are you sure? are you sure you said it loud enough? by postcards by elle

they still hate us by angelic dissent

Articles on how to confront far-right ideas on social media

Alternative titles for this piece

oh, so your company protects the far right? should we throw a party? should we invite elon musk?

to the creeps on my comments: fuck off!!!

what happens when ugly sluts have opinions